By Alex Stirling-Reed

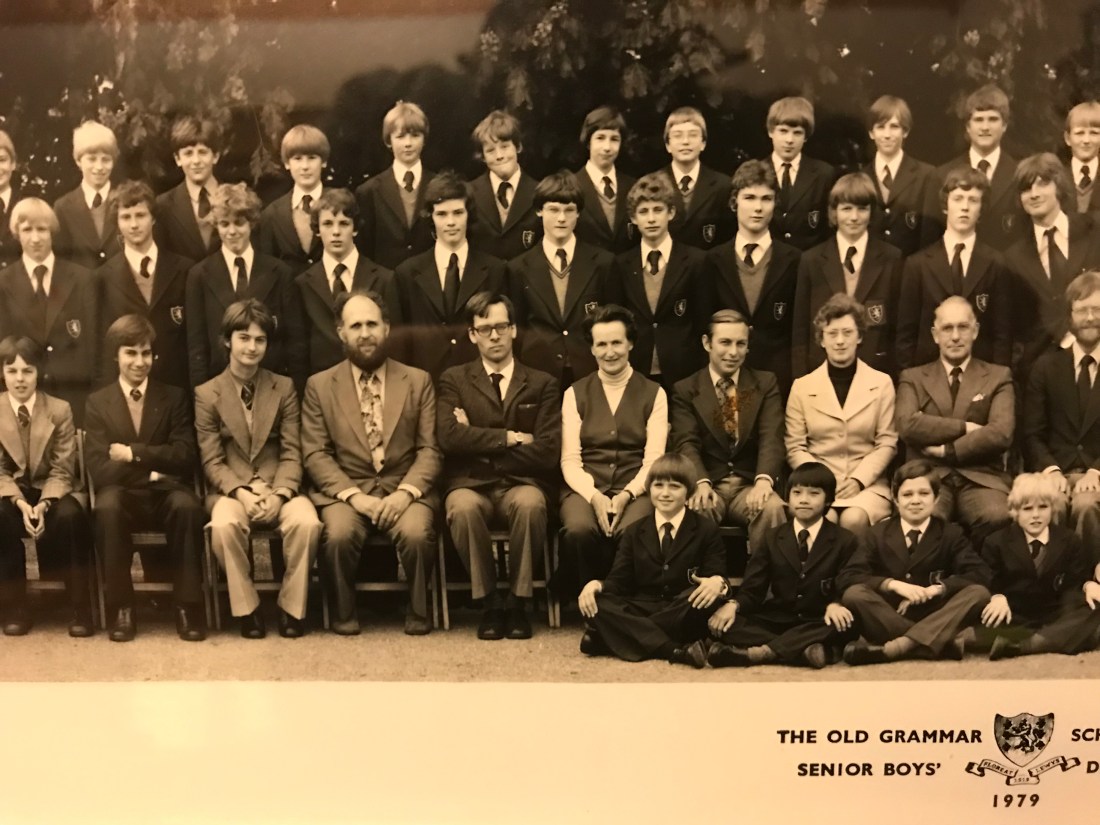

Having recently read the blog on life at LOGS from 79-85 I thought I would add a sequel comprised of my memories of the school I attended from 93-2000 – The Hodd years.

I remember the Lewes Grammar as a giddy, chaotic establishment, somewhere between a Dickensian School For Boys, full of antiquated rules and old, outdated morals and a lovable Roald Dahl cartoon character of a place, where it was more important to be seen to do the right thing, rather than to actually do it.

I began in the primary school and spent most of my days holed up in the attic, endlessly spilling ink on the carpets as we were forced, even aged ten, to write in clumsy fountain pens (presumably because quills were becoming hard to find in WH Smiths) The school had one computer which seems only to be used for one purpose – playing an 80’s game called “Magic Mushrooms” in which a blocky character collected other brightly coloured blocks for little or no reason. Technology being used educationally was obviously a priority.

The school seemed full of strange characters such as the ironically named “Mrs Bigg” who stood at about 3 foot tall and seemed to be well over 90, but was probably actually a little over 30. Break times were filled with thrillingly violent games of British Bulldog where 10 year olds would go to any length, including hospitalising tiny Reception children or tearing holes in other boys’ shirts, to stop the other team from reaching their piece of fencing at the end of the playground. I imagine many parents had to remortgage their houses to pay for an endless string of pricey Old Grammar blazers that had been torn from their innocent little Jimmy or Thomas’ back in the gaiety of the moment. That, along with trying to urinate as high as possible up the wall of the boys’ toilets, seemed to be the main pastimes. My only other memories of the junior school are of a teacher named Mr Elson who seemed to endlessly make us ‘silent cheer’ by patting ourselves on the back and of two trips, one to The Brickell’s farm where several children were lost in the corn for hours and an end of year trip to Sam Harris’ house, as he had the fortune to own a small indoor pool, which we all dutifully squeezed into. What a way to end our days in primary school! Private education truly is for the privileged.

In 1995 I reached the lofty heights of year 7 and begun my senior education in earnest.

The first thing a visitor would notice would be the noxious gas smell emanating from Mr Blackwell’s physics lab. This, combined with the fog of decades old cigarette smoke and a hint of strong alcohol in the air, made it hard to fully apply oneself in any physics lesson; or maybe it was just the dull “Adventures in Physics” DIY teaching booklets we were given to work through on our own from years 7-9? These were faded and had been created somewhere near the dawn of time to ensure than no real teaching had ever be attempted and so we kissed goodbye to any contemporary ideas that may have been discovered or explained post Renaissance and resigned ourselves to playing listlessly with magnets for the following three years. Any questions we had, I seem to remember, were directed at the smart kid in the class “Matthew Thacker” who really should have been on the pay roll as a substitute teacher. Occasionally Mr Blackwell would take us for P.E where he would stand barking army-style orders whilst chain-smoking King Size Benson and Hedges. It was inspiring stuff.

The other thing a visitor might notice as the entered the main entrance was the towering, red Coke machine, standing sentinel under the stairs. This attracted those fortunate enough (or not) to have the required 50p, like moths to a diabetes-inducing flame. If coke wasn’t your thing there was always the tuck shop at break where, if you could beg or borrow a few pennies, you were able to purchase any number of brightly coloured sugary treats. Some students used skittles as a sort of friendship currency. If you promised to be ‘Lobby’s friend’ for the day you would receive a sweaty handful of skittles from a bulging, rattling pocket. Lunch inevitably followed the tuck shop where all manner of nutritious treats awaited. “Meal of the day” seemed to be forever “chips and slush” served by dinner ladies still exhaling the yellowing smoke from the cigarette they had been smoking three feet from the food preparation area. As mentioned in the last blog, once a term a victim would be named as that term’s “Grovellie” as in you had to ‘grovel’ by donning your labcoat and serving glowering teachers such as Mr Main, affectionately known as ‘Gannet’ and Mrs Prior. Wackford Squeers would have been proud. I quickly worked out that if you spilt things or made a poor job of the whole business you were less likely to find yourself doomed next term. Others were not so wily.

After all that sugar and all those coma inducing chalk and talk lessons you would think we would have had a large area to tear about in. Perhaps a green field with trees to sit beneath to enjoy a stimulating discussion on the day’s hot topic? A tennis court to let off steam in? At least a playground bigger than the one we enjoyed playing British Bulldog in all those years before, surely? Sadly this was not so. In fact, I remember hearing a rumour that NASA were going to use our “playground” as a test run for landing on Mars as it was so deeply poker marked and uneven. At the top end were a ledge and a raised platform of sorts. Here boys would be positioned as the victims of the game alliteratively known as “wall ball”. I can still here the high pitched screams now as Craig Hanwell and his friends launched a volley of tennis balls at James Stalard. If anyone refused the game they were treated to a practice known as “wall hanging” which sort of speaks for itself really. No teacher ever seemed to be on duty to stop these Gladiatorial style games in all of my five years at the senior school. If, by chance, the tennis balls found their way over the walls into the next door garden (as they were wont to do) a small child was chosen and pushed forcibly over the wall to retrieve it. The wall had a much larger drop on the other side which made the return journey all the harder, especially as by the time the ball had been retrieved, everyone had inevitably forgotten they were there and had left them to struggle back to base camp alone. At the other end (if you can say a space of about six foot by six foot has ‘ends’) of the playground, sunk forbiddingly into the floor stood the mysterious hut where the unfortunately named Mr Gay and his…colleague? … Mr Vincent worked and – as was believed – lived. Both were men of few words and seemed to communicate in Neanderthal grunts. The only time I saw either of them move with any pace was when Mr Vincent physically pinned me against a wall by grabbing me by the front of my shirt and threatening me with his chisel.

P.E, thankfully didn’t take place in our Reading Gaol-like prison yard but rather happened either in a field behind the school known as “The Paddock” or at “Baxter’s”. To avoid the long three minute walk around to the entrance of The Paddock we used to tear ahead of Mr Turner, our omnipresent P.E teacher (who was for some unknown reason, rumoured to have only one testicle), risking life and limb by leaping over the wall and running down the vertical slope through the seven foot stinging nettles. The journey to Baxters was equally perilous, as you were forever having to negotiate the screams and curses of the “Window Witch”. The Window Witch adored the tiny concrete forecourt in front of her flat and it seemed that we did too. No matter how many times she threated to call Mr Anderson (a teacher who had retired in the mid 60’s) we never were able to resist the temptation of the sound of football boot studs on concrete. ‘Games’ was brilliant. All we ever seemed to do was play endless games of football, ten on each side and who cares about the skills! At the end of our two hour “lesson” we would return, via the forecourt having defeated the ever vigilant Window Witch for a second time, to the showerless changing room to drag our school trousers and white shirts over our sweaty, mud-caked bodies. In winter the pitch was frozen and our hands burned red with the onset of frostbite making it hard to do up the fiddly shirt buttons. Eventually, I abandon my P.E kit altogether and just opted to play in my school uniform instead, much to my mother’s dismay.

Perhaps the thing that most obviously set LOGS apart from of its contemporaries was the fact that all male students were made to purchase and carry briefcases. We were the original “briefcase wankers”. Whilst students from other schools in the 1990’s proudly displayed their ‘Slammin’ Vinyl’ or ‘Spliffy’ record bags we walked home like dwarfish businessmen minus the bowler hats. Briefcases never lasted long as some students tried to carry all of their books, exercise and text, in their briefcases in order to avoid forgetting to bring the right books to the right classes. Inevitably a hinge burst or Abraham Cambridge built Empire State Building-like towers out of them and in the 9/11 style crashing fall, something on them would break or tear off.

When I look back at my time at LOGS, I seem to remember only two emotions: firstly the frustration of battling what I saw to be old fashioned and pointless rules about how long your hair could be or what item of clothing could be worn in what part of the school, and secondly pure hilarity. I don’t think I’ve ever laughed as much since. Just the thought of a certain teacher or class can bring a smile to my face. Whether it was watching Mr Boyden struggling for hours at a time to look up all the random words that we had asked for in a German dictionary or trying desperately to get the huge box of a TV to work or seeing Mr Mitchell (Art) wander passively past a corridor in chaos, just pausing to mumble “carry on” before drifting off into the distance again. Whether it was hearing Dr Hodd, the headmaster no less! saying the immortal line: “I’ll have no gays in my school” or hearing Mr Blackwell roar “You again…I I I just don’t Beliveeee it” – it was an endlessly an entertaining place to be young.

Occasionally, the struggle of teaching a small class of thirteen year olds would become all too much and teachers would launch any objects they could get their hands on across the classroom in a Hulk-like explosion of rage. Two famous incidents include Mr Dumbavand throwing mini Casio keyboards across the class, as yet another sniggering student prodded the “demo” button and played the tinny tune of “The Entertainer” for what must have been the millionth time. The other involved Mr Ashford hurling breeze block-like chunks of off-cut timber and shouting “There’s wood here, and here and here.” Another occasion I remember a teacher really losing their shit was when a peer of mine by the name of Robert Bagley locked the aforementioned Mr Mitchell out of the school by quietly flicking the lock on the back gate. With interest, my friends and I all retreated to what we thought was a safe distance, not unlike a bomb disposable unit in Helmand Province, preparing for the inevitable. Silently we waited. At first there was a confused shove on the door, then an experimental small thump and suddenly, without warning the gate began to be battered and assaulted as a frenzy of blows rained down. We all stood transfixed waiting to see which would win, teacher vs. door. Whether he broke it down or not I don’t remember. Perhaps the school bell went and we all fled thankfully to the safety of lessons?

Other teachers/members of staff who deserve a mention are the loveable and eternally scruffy Mr Senior, also mentioned in the previous blog, who as well as being “hopelessly disorganised”, seemed to have no set job role and spent his days declaring “oh isn’t it marvellous” about everything and anything. The other is the equally kind Mr Wood (History) who was only ever able to frown for the briefest of moments, hopelessly trying to feign annoyance, before breaking out into a wide, slightly tipsy, looking grin. In some lessons we seemed to learn more from our contempories than the teachers. One afternoon, a pupil by the name of Phillip Brooke, who was an avid cadet, spent most of lesson explaining how The Allies could have crushed the Nazis with a clever two-pronged pincer movement. The teacher, Mr Knight, seemed at one point to eagerly taking notes -presumably in order to pass on this wisdom to the next class of students he had lining up at his door.

The building itself was more like a large, rundown house your crazy aunt lived than a school. Complete with secret staircases and dusty attics, some of the corridors were so tight that it was a struggle to pass other students even in single file. Frequent blockages often led to the timeless cry of “bundle” followed by the shrieks and pleas of any smaller student who had the misfortune to be passing by. One boy in particular by the name of ‘Dom Palmer’ could often be found at the bottom of these human mountains with arms and legs twisted at odd and unnatural angles.

The girls’ school was a far away, alluring land, fiercely protected by the red-haired dragon “Mrs Prior”. Humourless and jagged, Mrs Prior was all glares and buckteeth. She eyed any male within 100 yards of “her girls” with an air of deep suspicion and had an expensive card-activated lock put on the front door of the girls’ school to prevent any of us boys straying in that direction. With these draconian rules, combined with an almost non-existent sexual education programme, and the fact that we only had 8 girls in our year anyway, it’s a wonder that any of us red-blooded males entered 6th form with any knowledge of the female world at all.

For all the chaos and lack of structure LOGS was a great place to spend your younger years. A blind spot on the metaphorical Ofsted map, the 90’s must, surely have been the dying gasps of LOGS way of life. Despite the often poor quality of lessons, the lackadaisical behaviour management, the rundown facilities and the two hour daily commute on a stinking, tired bus, I wouldn’t change my time there for the world. Who needs an excellent education when you can say you spent your teen years laughing all day?